| The US Occupation of Iraq: Casualties Not Counted By Dahr Jamail t r u t h o u t | Perspective Thursday 05 October 2006 An anxious unrest, a fierce craving desire for gain has taken possession of the commercial world, and in instances no longer rare the most precious and permanent goods of human life have been madly sacrificed in the interests of momentary enrichment. - Felix Adler In all past wars the United States has been involved in, including the two World Wars, Vietnam and the first Gulf War, the military was self reliant and took care of its basic support functions like cooking, cleaning and other services. That changed when the Cheney administration took control of the government in 2000. War has now been privatized, and the shining examples of this privatization are Afghanistan and Iraq. As you read this there are approximately 100,000-125,000 American civilian contractors working in Iraq and Afghanistan. Their jobs range from providing security to desk work to interrogating prisoners to driving convoy trucks to clearing unexploded ordnance. A year back, in November 2005, the US Department of Labor listed 428 civilian contractors dead and 3,963 wounded in Iraq - none of which are ever counted in the official casualty counts. Employing civilian contractors supposedly saves money in the long run and, more importantly, frees trained soldiers for battle. The notion of low expenditure stemmed from the assumption that civilian contractors were hired for temporary/emergency engagements. This assumption no longer holds worth in the face of the current long- term (permanent) guerrilla war (read-Iraq and Afghanistan) without clear front-lines. Given the astronomical profits posted by these defense contractors, in addition to widespread fraud and waste, it is difficult to believe that any administration would want to adhere to this model, unless of course certain members of that administration were financially profiting from it. Those vague front lines stretch all the way back home, for it was at home that Tim Eysselinck became one of the thousands of uncounted and unaccounted-for civilian casualties in Cheney's so-called war on terror. Eysselinck worked for RONCO Consulting Corporation since 2000, and his last assignment in Iraq from August 2003 up to February 2004 was as the head of a de-mining team that was assigned to clear cluster bombs, land mines and other unexploded ordnance. A combination of this work, a perceived life-threatening airplane accident, and witnessing military personnel kill innocent civilians proved lethal for him. By the time he returned home to Namibia he was steeped in post-traumatic stress disorder. Two weeks before his death, he told a friend in Namibia, "There was a lot of death and murder going on [in Iraq] that was just not right, and the only thing they could do was to follow orders." He also told her, "I should go back." For nine years, Eysselinck had served as a captain in the US Army and was very proud to be a member of the Armed Forces. He had been commissioned as a Lieutenant of Infantry from the ROTC at the University of Florida on completion of his BA. He was a graduate of the Infantry Officer Basic course, Airborne School, and was Ranger qualified. He had served as a Platoon Leader, Company Executive Officer and Battalion Adjutant in a Light Infantry Division based in Hawaii. After four years he was promoted as Captain. Before leaving he gave up Active Duty. In 1994 he returned to serve with Special Operations Command Europe and was deployed to Bosnia, West Africa, and finally Namibia in 1998. Throughout his military career, Captain Eysselinck received excellent Officer Evaluation Reports. LTC Nichols, Director of SOCEUR, wrote of Captain Eysselinck: "Absolutely outstanding. Top 5% of all the officers I have every known. Top pick for line Battalion Command. Performs exceptionally under mental stress." Eysselinck's rating comments for his 1998 posting in Namibia as military liaison officer included the following: "Captain Eysselinck has once again demonstrated why he is on our very short list of Reserve Officers who can be relied upon to complete real world missions." He left the army in 2000 because his wife, Birgitt, had made that a condition of their marriage. But when he returned home from his time in Iraq, Tim was a changed man. His mother, Janet Burroway, is a writer and academic who lives in Florida. In an earlier interview with journalist Rick Kelly, she described her son on his return from Iraq thus: "What he experienced had a shattering effect on him. There was absolutely no hint of the depression to come. But the anger was palpable. It was shattering to him, to come to feel that the war was wrong. He spoke of corruption, lies, greed and a brutish stupidity. At the time, I was so happy to hear that he had seen something of what I felt about the war that I didn't stop to think about how deeply wounding that would be to him. He said that he was disgusted with the Bush regime, and that Bremer had screwed it all up with the Iraqis. He was always, almost glibly, willing to die for his country, and even saw himself as going heroically into battle. But that's not what happened to him. He said at one point to a friend in Namibia that he was ashamed to be an American. I'll say that any day of the week, but for Tim to say it represents such a huge turnaround." His wife Birgitt told the same journalist that during his Christmas break in December 2004, her husband had discussed the atrocity he was witnessing in Iraq. She feels this must surely have contributed to his PTSD: "He also said that another time they were driving behind, or with, a military convoy that just started shooting into the civilian houses. And he said, 'Then they try to deny it when civilians are killed.' And he said the military does not have to pay compensation, and he said it with sort of a smirk, like he was saying: 'typical.' They [contractors] were shot on at the site. There were improvised explosive devices placed alongside the roads that they were using, the sites where they were working. One of his colleagues was crippled by a blast - these are all things now that they are trying to pretend didn't happen. They should at least write a certification that if somebody comes out of a war zone they [contractors] need to be debriefed. You can't just let them back to an unsuspecting family and society. Back in Namibia, we weren't prepared for this. We don't even know what post-traumatic stress disorder is. If I had a clue about what it was, I would have sent him to a doctor immediately, because he had the signs." And like Tim's mother, his wife too had noticed that it was a changed man who returned from Iraq. "There were changes. The biggest change was his sleeplessness," she told Rick Kelly, "And he had this uncharacteristic hyper- vigilance - locking the doors, making sure both safety gates are closed. Tim was driving recklessly, physically trembling at times and repeatedly blinking his eyes. He was irritable, anxious and displayed uncharacteristic outbursts of anger on his last day. At the end, he was watching the news quite obsessively and writing to his men almost every second day, which I only discovered afterwards. He was asking how they are. When the Lebanon Hotel blew up, he writes, "Are you OK?" You know, this type of thing: "I watched the news with trepidation, I hope you take care. Worrying about you guys, hope you made it through the recent bombings." He obviously had soldiers' guilt, or survivors' guilt, whatever you call it. In a state of shock and disillusionment about a war he had previously supported, 40-year-old Eysselinck committed suicide at his home in Windhoek, Namibia, shortly after he had returned from Iraq on a three-month leave of absence in agreement with RONCO because he felt "over-stressed" after two years in Ethiopia and then Iraq. It turns out that while working in Iraq, a major stressor for Eysselinck was the persistent attempts by RONCO headquarters to disarm him and his team in Iraq with a view to avoid potential liability. This had become an ongoing struggle, even after other contractors who had been unarmed were killed, ambushed and severely beaten. Eysselinck had threatened to quit if they disarmed him. Five minutes before Tim killed himself, while holding up the US military-issued Iraq's Most Wanted playing cards, he told his wife, "You get me professional help." Birgitt had said in her interview with Kelly: "He knew something was wrong. Three weeks before, he woke up and said to me, "Something is wrong with me, I'm feeling down." But what was I to do with that statement? Feeling down? I also blame myself in a way, because I don't have any knowledge of depression, I know nothing about the subject. I mean this was a clear and obvious symptom. And then he said it again a week later - that he couldn't sleep and was waking up three times a night." Around noon on the day of his death, in the presence of the housekeeper, Tim said he was depressed. Later the housekeeper recounted she had seen him marching through the house like a soldier. With Tim's death began a nightmarish journey and legal odyssey for Birgitt. RONCO refuses to acknowledge that Tim's work caused his PTSD and refuses to pay her any compensation for Tim's death. She initiated legal action to qualify for support from the CNA International insurance carrier under the US Defense Base Act. RONCO responded to her efforts to first establish Tim as a war casualty and then to get justice by not acknowledging any of it. Not only did the company turn a cold shoulder, they even went out of their way to discredit him, adding to her anguish. It is important to note that among RONCO's full-time employed staff of 90 US and 300 host-country personnel, the company has many ex-government officials, including a former USAID deputy assistant administrator, mission directors and retired senior military personnel. Their clients include USAID, the US Department of Defense and Blackwater. The company has been awarded contracts in Iraq worth well over $10 million. Birgitt recently told me that three days after Tim's death, she had received a call from Stephen Edelmann, the president of RONCO. "He expressed his condolences and wanted to know what happened and concluded that "It [Tim's death] was nobody's fault ... it's a defective gene." Reportedly Edelmann had also said that RONCO was too small a company to have a pension scheme." Birgitt told me that RONCO sent a wreath to the funeral. Her disillusionment showed in her words: "This was the sum total of their assistance to a man who worked from them since November 2000 as a Deputy Task Leader in Namibia, then as Chief of Party in Ethiopia, and someone who finally put his life on the line to establish their projects in Iraq." Roughly three months later, Tim's mother wrote RONCO a letter, with a psychiatrist's report attached, requesting compensation from the company. RONCO realized it would not be able to wriggle out of paying $3,300 that they owed Tim for unused vacation time. To Tim's mother's claim they replied that Tim had been a valued member of their team and referred the family to a lawyer with whom to file a DBA claim. It is also clear that RONCO has no debriefing infrastructure for their employees who return from Iraq. As Birgitt said, "The point is that they should have debriefed their people. They can't send people into a war and then not take care of them properly. I sent a happy, healthy man to Iraq. We had no problems, no marital problems, no family problems, no money problems - no problems. So evidently, this [Tim's PTSD-induced suicide] was caused by the war and what happened there." Five months before his death, on 16 November 2003, Tim wrote the following email to his stepmother: "Talked to Ben tonight and he said that you were worried about me. Don't, I have a deal with Birgitt that if things got bad here I would be brave and be a coward and run away. I would never consider this if I was in the military, but I'm smart enough to know that I don't have to be here and I have way, way too much to live for to take anything but a well-calculated risk with my life. I have a son and daughter to marry off and both of them need me more than this place. So again, I'll be brave and be a coward, if I feel that my security is really at risk. In the mean time, I've trained 100+ Iraqis that can maybe make a difference and save a few lives. You can't really argue with that as an accomplishment." But his perception evidently changed after RONCO went operational in November 2003. That is when Eysselinck and his team of international trainers accompanied Iraqis to multiple task sites daily; going through checkpoints around Baghdad to do Battle Area Clearance of live munitions. On 10 January 2004, Tim wrote in his diary: "Everything crazy now. I hope I can make it home safe." The diary entry included detailed doodles of bombs, rifles, aircraft, gas masks and rocket-propelled grenades. Is there something we have forgotten? Some precious thing we have lost, wandering in strange lands? - Arna Bontemps When the claims case came up, instead of taking responsibility for negligently causing the irreplaceable loss of a beloved husband, father and son, and apologizing for the severe emotional damage inflicted upon his family and friends, RONCO introduced into evidence a scurrilous fabricated attack on the character of its deceased employee whom they had themselves entrusted with their most difficult and profitable project. Among other things, the deceased Eysselinck was accused of being rude, uncaring and indifferent; a military Ranger "wannabe" who "was only a tab wearer but never saw combat." This depraved "defense strategy" compelled his widow to obtain statements from over 16 witnesses, including a statement from the Namibian Defense Force, in order to rebut the allegations made about Tim by a RONCO employee. RONCO then hired an 82-year-old retired psychiatrist, who when interrogated admitted to not having read current research on PTSD, to falsely claim that the onset of PTSD symptoms occurs immediately after the traumatic event and that suicide is an outcome of depression rather than PTSD. After their efforts to discredit Eysselinck backfired, RONCO set out to denigrate his work and the very nature of the war in Iraq. Two RONCO workers made the incredible claim that conditions had been far from dangerous in Baghdad between August 2003 and February 2004. They also claimed that Tim had not been exposed to threats. They made these claims, along with testifying that neither of them had seen Tim during that time. There was and continues to be overwhelming evidence from work reports in the country that are contrary to these fictitious and bogus claims. It appears that RONCO is more concerned with evading potential liability and sustaining their profit margin than with the safety and well-being of their employees. Tim was never diagnosed with PTSD before he died so there is no hard evidence that he had PTSD. The reason there exists no irrefutable evidence of his having PTSD is RONCO's criminal negligence in failing to provide psychological screening and counseling to a staff member who spent seven months in a war zone. According to the Army Center for Health Promotion and Preventive Medicine, the suicide rate in the US Army in 2005 was the highest since 1993. Almost 1,700 service members returning from the war in 2005 said that they harbored thoughts of hurting themselves or felt that they would be better off dead. Over 3,700 said they had concerns that they might "hurt or lose control" while with someone else. In July 2005, the US Army Surgeon General, Lt. Gen. Kevin Kiley, announced that, according to a survey of troops returning from the Iraq war, 30% developed mental health problems three to four months after coming home. This is in addition to the 3-5% diagnosed with a significant mental health issue immediately after they leave the theater, and 13% experiencing significant mental health problems in the combat zone itself. For decades, it has been an undisputed medical fact that the onset of PTSD is not immediate after the traumatic stressor. This is why the US Army has a policy to debrief troops on their return from the war zone and of checking back in with them six months later in order to check for signs of PTSD. Tim's family never thought they would have to prove in court the obvious fact that it was dangerous to work in Baghdad during the occupation and the truth that their deceased loved one had faced threats sometimes on a daily basis, not to mention that his job entailed handling unexploded ordnance. Tim worked on the task sites daily and was exposed to the very real threat of being killed while handling unexploded bombs and mines over and above the daily security hazards that all contractors in Iraq face. Nevertheless, the judge in their case did not agree with the family and the professional opinion of their psychiatrist, despite the fact that the judge had found Eysselinck to have been "a person of high moral character much loved by family, friends and co-workers," "patriotic, a perfectionist, polite and fiercely honorable," and "a devoted husband and father who was respected by fellow workers and trainees." A human person is infinitely precious and must be unconditionally protected. - Hans Kung And one is left to wonder how many more Tim Eysselincks there are in Iraq? How many more of them have returned home not knowing about PTSD or how to treat it? How many of their families are currently unnecessarily at risk from the often volatile behavior caused by PTSD or are left in the bereft position that Birgitt finds herself in? Civilian contractors in Iraq, though they are paid handsomely for their time there, are easily lost in a legal no- man's-land if tragedy strikes. Their families are then left in the lurch as well. With an estimated 100,000-125,000 American contractors in Iraq and Afghanistan, we can safely assume there are thousands of stories similar to Tim's and still counting. To each story is attached an individual and a family. And the occupation grinds on with no end in sight... An interview with the mother and widow of a former Iraqi contractor “I feel that there has been an enormous betrayal of truth and principle” By Rick Kelly 10 March 2005 Tim Eysselinck worked for RONCO Consulting Corp. in Iraq between August 2003 and February 2004. He headed a de-mining team that was responsible for the clearance of land mines, cluster bombs and other ordinance. Tim developed post-traumatic stress disorder, and his experiences in Iraq left him disillusioned with the war that he had previously supported. On April 21, 2004, he committed suicide at his home in Windhoek, Namibia, two months after he had resigned from RONCO. He was 40 years old. On January 6, the World Socialist Web Siteinterviewed Tim Eysselinck’s mother, writer and academic Janet Burroway, who lives in Florida. On February 2, the WSWS spoke with Tim’s widow, Birgitt Eysselinck, who lives in Namibia. World Socialist Web Site: I understand that Tim was attracted to the military from an early age. Janet Burroway: Yes, he was intensely patriotic. I kept trying to explain it to myself. His dad and I had been liberals. My parents were not. My dad was really a Taft republican. He believed in pulling yourself up by your bootstraps. He had a powerful work ethic. It seems to me that Tim, I don’t know if was in his DNA or he picked it up somehow, but it was part of his rebellion from his liberal father and me. It struck me as funny, because my brother and I had rebelled to the left. Out in the demonstrations, with the kids in the strollers—we were ’60s kids. We were a little older, but that’s where our sympathies lay. Tim studied history at the University of Florida, where he joined the Reserve Officer Training Corps, which helped put him through college. Then he was in the army for four years as a captain. He was mainly stationed in Hawaii. He was fiercely proud of being in the army. He later worked for [security company] Wackenhut in Cameroon. From there he joined the army reserve, which had a great effect on his life. He volunteered for everything he could volunteer for as a reservist. He went at one point to Congo, and later to Bosnia. He then went to Namibia in 1997, where he was running the office part of a de- mining operation, the field part of which was run by RONCO. WSWS: And he later went to Iraq with RONCO. JB: Yes, there were 90 Iraqis on his team and I think eight or nine Americans, or coalition—I think there may have been an Australian among them. I used to say to him that I feel very lucky that since you and I have this political difference, what you are doing is essentially a soldier’s job, but it’s one of which I can 100 percent approve. He smiled at that. He understood that it was a piece of luck for me. We had always trod this ground carefully, the political ground. We understood pretty well that there were areas in my thinking that were alien to him, and areas in his that were alien to me, and we were able to acknowledge that...and I think we loved each other very much. But I knew that if Tim had been told to put mines in the ground he would have put them in with as much alacrity as he took them out. He felt that he was doing something for the US government, and that’s what he wanted to do. Over the years “my country right or wrong” was just a theme—and then it wasn’t. A couple of days after 9/11 we were on the phone, and he said, “I just think that Bush is doing a fabulous job.” I didn’t answer. We didn’t really have a political discussion for two years after that. Why spoil a beautiful relationship? It was a year ago yesterday that I last saw Tim alive. In the couple of days he was home he let me know he’d changed. He was intensely angry at the Bush and Bremer regimes. I was absolutely bouleversé [knocked over]. My brother said that Tim was someone who thought that with ideals and a gun you could fix things. WSWS: How did his experiences in Iraq change his views on the war and the Bush administration? JB: What he experienced had a shattering effect on him. There was absolutely no hint of the depression to come. But the anger was palpable. It was shattering to him, to come to feel that the war was wrong. At the time, I was so happy to hear that he had seen something of what I felt about the war that I didn’t stop to think about how deeply wounding that would be to him. He said that he was disgusted with the Bush regime, and that Bremer had screwed it all up with the Iraqis. I know that he later said to someone in Namibia that there was murder and killing going on that should not be, but he didn’t say that to me. Had I known that it was my last chance to talk to him about it in person I would have pressed him, but I deliberately did not. One of the things he had always praised me for was that I let him be himself. I thought that this was a big change for him, and I didn’t want to alienate him. WSWS: The fate of private contractors in Iraq is another area in which the US authorities are suppressing as much information as they can. JB: This is a point of bitterness for me. I don’t think that he is counted among the dead of this war, and I know that he is. And I also think we don’t count Iraqi lives as being as valuable as the Americans. I feel that there has been an enormous betrayal of truth and principle. And that Tim and I, and Birgitt, are caught up in this particular historical moment—that we have been betrayed. This is where the anger comes in. I have spent my life, and my son did too, believing that whatever else, means must be consonant with ends. And that’s not what we’re seeing our country do now. And I think that one place where we connected is the anger and disappointment at that. He was always, almost glibly, willing to die for his country, and even saw himself as going heroically into battle. But that’s not what happened to him. He said at one point to a friend in Namibia that he was ashamed to be an American. I’ll say that any day of the week, but for Tim to say it represents such a huge turnaround. I now regret that I didn’t bring up the subject of Bush and the war when I spoke with him on the telephone after I last saw him. But I didn’t want to sound like, “I told you so.” I talked about my life and asked him about his and did not introduce anything political. WSWS: What are your thoughts on the current political situation? JB: The presidential election was a dilemma for me. My husband said that he was going to vote for the Green Party, and I said, “Don’t do it, don’t do it, we’ve got to get this guy out of here.” I have been feeling for about two or three years a kind of dismay. It has come to seem to me, fundamentally, that democracy and capitalism can’t coexist, because ultimately if the bottom line is the bottom line then you can buy an election. And that’s what we’re seeing played out. You will understand that I was very glad to see the last of 2004—when I look at that year, it seems to me that the personal calamity is the biggest that I have ever faced, and then the global calamity with the tsunami is the biggest we’ve faced. Who needs a war? What’s going to happen? How can it be saved? How can the Iraqis be saved? I am glad that Kerry is not having to deal with this, because there’s certainly nothing that he could have done. WSWS: But Kerry and the Democratic Party were just as committed to the war as was Bush. The essential political task facing working people is to break from the Democrats and Republicans and build their own independent political party. Like you, many people were drawn into supporting Kerry as the “lesser evil,” but this has proved to be a failed political perspective. JB: I agree absolutely. The Democrats feinted to the center, and the center pulled to the right. What I hoped for was that the Democrats could counter the simplistic reasoning and rhetoric—all that “right or wrong,” “with us or against us,” “dead or alive.” But Kerry just made complexity as fuddled as the voters thought it was. When corporate corruption becomes too obvious, then the GOP trumps up a hot-button “moral” issue as a distraction. What you end up with is a language of statesmanship that is all, all lies: no child left behind, freedom in the Middle East, compassionate conservatism, family values, ownership society. Ownership society! A euphemism for institutionalizing greed, just as “collateral damage” and “soft target” are euphemisms for killing people. When do we start telling and hearing the truth? WSWS: How are you dealing with your grief now? JB: It changes all the time. I was thinking about this in terms of the tsunami and the Bonsai Pipeline where Tim was stationed in Hawaii when he was in the army. What occurred to me is that something like this is not like a tsunami; it’s like the Bonsai coastline. It comes at you in waves, and it does it for much longer than you expect. It doesn’t overwhelm you and then recede gradually. Christmas week I astounded myself by being fine. Tim loved Christmas more than anybody I ever knew, and I was thinking about him all the time, but I got caught up in my own routine of celebration and we went to parties and we had presents and had a fine time. And then this anniversary of his having been here for the last time—it’s just really hard. So, the answer to your question is, I’m doing fine. I’m not suicidal and I’m working every day...and I love him very much. * * * WSWS: Why did Tim go to Iraq? Birgitt Eysselinck: I met Tim in 1998 when I was a national information officer with the United Nations. He then worked in Ethiopia for two years, after which he was offered a post in Washington, in the headquarters of the company [RONCO]. There was a little disagreement about the relocation costs. The company, making mega- profits, wanted to offer him only the plane tickets for the family to America—but no other relocation costs. He was very unhappy about that, because he found out how much profit they were making. So there was a disagreement about that. And a little bit of a stand-off. And then they offered him Iraq, and he looked forward to it because he was heading the biggest project they had. The situation was calm in Iraq. It was just after the major combat was over, so there were no snipers and insurgents, etcetera. So I agreed, but only for the start-up. He only wanted to get it running, because he had always told RONCO that he wanted a family posting. They knew that very well. We discussed the invasion very often. I was completely against that war. I thought it was based on a lie. I remember in Ethiopia we discussed it, together with other friends. And when we were saying that it was all lies, that they wanted the oil, he said, “The Pentagon doesn’t lie; they wouldn’t send our soldiers in there if it’s not true.” He was totally convinced that they would find the weapons of mass destruction. WSWS: And then he discovered that it was all a lie. BE: Yes. There was a cartoon published in a Namibian newspaper here, after they caught Saddam. They were looking in his mouth and saying: “So Saddam, where are the weapons of mass destruction?” That was published in December when he came back for Christmas. And he thought it was funny. But when my sister asked him what he thought of it when he came back from Iraq, he was very rude to her. He said to her, “I still don’t get it,” and walked off. It was strange because he wasn’t like that. He was never discourteous or brusque, or anything like that. He just walked away. So yes, it definitely had an effect. He said to a friend of mine that he was disillusioned with the war and that he was ashamed of being an American. And that was about two weeks before he put a bullet in his brain. He had called me almost every evening from Iraq. There was often rocket fire in the Green Zone. I even heard it over the phone. He told me about two particular incidents. He said that once they had a near-fatal car accident, involving a coalition SUV. And he said that if they had turned as they had intended to they would have been dead, because their car would have been smashed. The SUV came past them at high speed. He also said that another time they were driving behind, or with, a military convoy that just started shooting into the civilian houses. And he said, “Then they try to deny it when civilians are killed.” And he said they don’t have to pay compensation, and he said it with sort of a smirk, like he was saying: “typical.” They were shot on at the site. There were improvised explosive devices placed alongside the roads that they were using, the sites where they were working. One of his colleagues was crippled by a blast—these are all things now that they are trying to pretend didn’t happen. And on Tim’s last flight out of Baghdad he said that he thought he was going to die after he heard explosions. These turned out to be defensive flares, and the plane hadn’t been hit as he imagined, but it was extremely stressful for him. The other thing one has to look at in relation to his illness is contamination. There are hundreds of pictures of bombs and fuses in Taji West, which was an ammunition-storage place of Saddam Hussein. Tim took pictures— close ups, with the serial numbers visible. In some of the pictures, he’s holding fuses and things in his hands. And they’re not wearing any protective gear. I have a picture—with bare hands they’re doing this work. The US military subcontracted this work to a private company. They’re trying to privatize their war, to fight it on the cheap. They should at least write a certification that if somebody comes out of a war zone they need to be debriefed. You can’t just let them back to an unsuspecting family and society, back in Namibia. We weren’t prepared for this. We don’t even know what post-traumatic stress disorder is. If I had a clue about what it was, I would have sent him to a doctor immediately, because he had the signs. WSWS: What were the symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder? BE: There were changes. The biggest change was his sleeplessness. And he had this uncharacteristic hyper- vigilance—locking the doors, making sure both safety gates are closed. At the end, he was watching the news quite obsessively and writing to his men almost every second day, which I only discovered afterwards. He was asking how they are. When the Palestine Hotel blew up, he writes, “Are you OK?” You know, this type of thing: “I watched the news with trepidation, I hope you take care.” He obviously had soldiers’ guilt, or survivors’ guilt, whatever you call it. You know, feeling he’s letting them down. He said to me, “You get me professional help,” just five minutes before he shot himself. He knew something was wrong. Three weeks before, he woke up and said to me, “Something is wrong with me, I’m feeling down.” But what was I to do with that statement? Feeling down? I also blame myself in a way, because I don’t have any knowledge of depression, I know nothing about the subject. I mean this was a clear and obvious symptom. And then he said it again a week later—that he couldn’t sleep. WSWS: I understand that RONCO has refused to pay you any compensation for Tim’s death, and that you have had to begin legal action in order to qualify for public money under the US Defense Base Act. BE: This company has the attitude.... They’ve just washed their hands and walked away. [RONCO issued a statement to the World Socialist Web Site that read, in part, “RONCO has an outstanding benefits program for its employees and their families. At the time of his death, Mr. Eysselinck WAS NOT an employee and thus, his family was not eligible for the benefits.... While, extremely sad and regrettable, the fact of the matter is that it is impossible to ascribe rational motives to irrational acts.”] (This statement is very interesting considering Ronco's employee's continue to get screwed under this outstanding benefits program 3/17/2010 ) Janet wrote a letter to the company’s president attaching the psychiatrist’s report that said his death was clearly a result of the work, and she wanted to know about outstanding leave money, profit sharing, etcetera. [A Namibian psychiatrist posthumously diagnosed Tim with post-traumatic stress disorder after assessing statements from family and friends, his correspondence, and other documents.] They only then got going and realized they owed him over US$3000 in outstanding leave money. Their whole attitude was that this is nothing to do with us any longer. They did refer me, to give them some credit, to my lawyer who’s handling the DBA [Defense Base Act] claim. But if this is successful, then the American taxpayer will end up paying for it—not them, out of their outrageous profits that they make. That’s not even the point—the point is that they should have debriefed their people. They can’t send people into a war and then not take care of them properly. I sent a happy, healthy man to Iraq. We had no problems, no marital problems, no family problems, no money problems—no problems. So evidently, this was caused by the war and what happened there. WSWS: What do you think about the international political situation? BE: I cannot support anything that goes against the most basic tenets of justice—and that is innocent until proven guilty. They went in there based on a lie, and you cannot make that a precedent in the world where the mightiest power can just go into a country on a false pretext. No matter what they achieve afterwards. That is my attitude and that will stay my attitude. What I think is really terrible about the Bush administration is the way they treat their soldiers. Essentially, Tim was a soldier and that’s why they offered him that position. One in six of their soldiers coming back have this problem of post-traumatic stress disorder, but they do nothing. They didn’t even attend Tim’s funeral. The embassy didn’t even send somebody to the funeral. This whole attitude about people being used as commodities and then thrown away once you’ve used them—this mentality of war in general—I have a big problem with that. If I look at what’s happening in my case, but also in other cases, I find this disdain for human beings. As long as they can continue making profits they’re happy. Court slams bank over ties to known crook By: WERNER MENGES PERSEVERANCE, even after death, in a fight against the might of one of Namibia's largest financial institutions finally paid off for a former Windhoek resident, the late Tim Eysselinck, last week. A dispute that started in February 2001 as a courtroom tug-of-war over the ownership of a vehicle that Standard Bank Namibia'sStannic division repossessed from Eysselinck, despite the fact that he had paid for it in full, ended in a bruising defeat for the bank in the Supreme Court on Wednesday. Not only did Eysselinck succeed with an appeal against a High Court judgement through which the bank managed to hold on to the vehicle, but he also won the case with Stannic being ordered to pay his legal costs. To add insult to that financial injury, the bank was also at the receiving end of withering criticism over its business ties with a known fraudster, fugitive car dealer Ockie Pretorius, in the rulingwritten by Acting Judge of Appeal Bryan O'Linn. Eysselinck died in Windhoek in April this year. By that time he had already had an appeal noted against the High Court judgement that went against him and in favour of Standard Bank in September last year. After his death his wife, Birgitt Eysselinck, decided to continue with the case that he had fought tenaciously, believing that the basic principles of justice would ultimately vindicate his quest. "Let that be his legacy. Because this may prevent these big business institutions from being ruthless and predatory," she commented on Thursday. She said her husband had fought the case as a proverbial "little man", standing up to a large and powerful financial institution, because he believed that justice would be on his side. He was not the ordinary sort of "little man", though. Unlike most people she and Eysselinck managed to pursue the case for close to four years, at a staggering cost of about N$360 000 in legal fees, she said. In the High Court justice was not to be on Eysselinck's side, but where it ultimately mattered most - in the Supreme Court - a unanimous verdict from Acting Chief Justice Johan Strydom, Judge of Appeal Pio Teek and Acting Judge of Appeal O'Linn made Eysselinck merge as the big winner, and Stannic as a humbled loser. A 1999 model Toyota Hilux four-wheel-drive bakkie was the bone of contention between the late Eysselinck and Stannic. Eysselinck bought the vehicle from a company owned by Pretorius in October 2000. By January 2001 he had paid Pretorius in full for the vehicle. In late February 2001, Stannic sued both Pretorius and Eysselinck to have the bakkie returned to the bank. Pretorius had bought the vehicle with financing from Stannic, but had not paid the bank in full before he sold it again, with the result that the bank claimed that the car in fact still belonged to them. At that stage a house of cards that the high-flying Pretorius had built in Namibia was collapsing, leading to his overnight departure from the country. Pretorius was trailed by numerous allegations of fraud. Only during the hearing of the case between Stannic and Eysselinck in the High Court did it emerge publicly that the bank had been forewarned early in April 2000 already of Pretorius's past record of similar crooked business dealings. Last week the bank's knowledge of the dubious character of their one-time valued client Pretorius, and their failure to act to safeguard assets involved in their business relationship with him, proved fatal for their case in the Supreme Court. Standard Bank had over a long period of time contributed to Pretorius's fraudulent representation that the bakkie was his to sell, Judge O'Linn found. In that time, it for instance gave Pretorius generous overdraft facilities without checking up on his claims of future earnings - claims that ultimately proved to have been phantoms and lies. The bank was in the first place "grossly negligent" in granting Pretorius an overdraft on the basis of a false claim of future earnings by him, the Judge stated - and that was one of the milder terms of criticism against Standard Bank. Acting Judge of Appeal O'Linn also put it in much stronger language. For a respected financial institution there might be few verdicts more embarrassing and damaging than being found to have been in cahoots with a known crook and fraudster. But that is, in effect, just the sort of conclusion that the Acting Appeal Judge arrived at. By giving finance to Pretorius, by not blowing his cover as a crook after the bank had been informed of his record in April 2000, and by not taking steps to see to it that Pretorius did not repeat known past conduct by selling a vehicle belonging to a bank before he had paid for it, the bank was aiding and abetting him, and connived with him, the Judge stated. If ever there was a case where "compelling considerations of fairness" would preclude an owner, such as the bank, from asserting his ownership rights, it was this case, Acting Judge of Appeal O'Linn concluded. Eysselinck was represented throughout this almost four-year-long court odyssey by Raymond Heathcote and attorney Tobie Louw. Dave Smuts, SC, instructed by Francois Erasmus, represented Stannic. My Son, My Soldier, My Sorrow In three essays written over 20 years, a liberal, pacifist mother struggles to understand her conservative son, a proud soldier and member of the NRA. By JANET BURROWAY Janet Burroway, a novelist, essayist and playwright at Florida State University, recently submitted an essay about her son, Tim, to Floridian. The piece is powerful on its own, but we felt it was even more affecting when read along with Burroway's earlier writing about her family. Here, then, are three essays, the first published in Floridian in 1984, the second in a literary journal in 1997. The third was written last month and sent to us a few days ago. - MIKE WILSON, Newsfeatures editor ESSAY I I have two sons, and where they come from, God only knows. All parents say that, more or less. My sons are so unlike each other that it isn't possible they were produced from the same two sets of chromosomes, which they were, nor that they were raised under the same single-parent effort of Spock and spaghetti, which they were. All parents say that more or less, too, but in my case it's really true. No, it really is. Tim is 20, Episcopal, Republican and polite. He would like fondu bourguignon for dinner, thank you, and if possible a Harris tweed topcoat for his birthday. At the moment, his head is shaved because he is at Fort Benning learning how to jump out of airplanes with Army ROTC cadets. Alex is 17, sloppy, barely scraping through British comprehensive school and a radical-left wing-feminist-anarchist. He can live on a loaf of bread and a 4-pound Edam cheese for a week, and he would go without that if it would get him an original Gibson semiacoustic guitar. His head is shaved except for a shield-shaped patch on top, the long forelock of which is bleached and waxed out over his forehead like the visor of an organic baseball cap. Mind you, even apart from baldness, they would look quite a lot alike if Tim were not wearing the alligator shirt with his yellow Sun Britches and his Top-Siders, while Alex has got one sleeve ripped out of his famous dead bird T- shirt and a single cricket leg guard over his shredded jeans. Seeking similarities, I note that they both like combat boots, but Tim's are intended for combat, wherever the sovereign United States cares to send him, whereas Alex's are for busking around the monument at Piccadilly Circus, where American tourists sometimes slip him a pound note to take his picture as a souvenir of London. (He left Florida last fall.) Tim, who thinks all Communists deserve slow torture, is personally a peacemaker, easygoing as a housemate and empathetic in a crisis. Alex, who believes in universal brotherhood and boasts that he's a wimp, can stir emotional turmoil and wreak physical havoc in any room big enough to hold two adults and a ghetto blaster. They are both proud of their Scottish heritage and the grandmother who was "purebred McKenzie," but of the two McKenzie mottos, it's clear Tim espouses the Celtic that translates "All for the King," whereas Alex and I wear the Latin badge "Luceo non uro," meaning "Light, not heat." You will have figured out that I love these kids. If you have also raised a human offspring to as many as 14 candles, you will also perceive that it's too late for me to do anything. Whatever it is, I've already done it, and I can't for the life of me figure out what it was. All parents say that, too. The only thing that saves a mother who can't keep the very hair on her children's heads is to have a theory. And this is mine: What I have got here is a microcosm of the generation. Tim is the son of '60s folks, like most of his conservative peers. We were the ones who had them out in strollers at the sit-ins and parked them in the playpens while we addressed envelopes for Mothers Against the Bomb. Tim being a peaceable and well-intentioned son, when it came time for his rebellion, he didn't want to cause any trouble in the family, so he just quietly adopted all the values that were dear to John Wayne and anathema to his father and me, and he went off to the privacy of the voting booth to pull the lever for Reagan. That's not only his democratic right, you see, but it leaves me in a beautiful double bind. How can a truly liberal parent dictate what a boy is to believe? You opt for Dr. Spock, and you turn out Mr. Spock. Is anybody out there saying amen? I thought so. But Alex is the other part of what's happening in the '80s teens. It's no use rebelling against Mom, who is clearly going to sit there and take it - if she'll let you be a soldier, she'll let you be anything! - so big brother gets to represent Big Brother. All those Steves and Kimberlys in their blow-dried hair! All those rosebuds at the bloody prom and those jocks with their polished sports cars! Now there is something a rebellion can sink its teeth into! And then what do we get out of it, we '60s parents - all that patience, all those withholdings of the rod, all that empathy with the flinger of spinach and solemn discussion of the current tantrum? I'll tell you. We get openness. We get communication. No sneaking about, no heart-hammering lies, no fear that the worst of the truth will bring down wrath. Don't get me wrong. I don't mean them. I don't fool myself that I know what's going on in their heads and hearts, in the bars and the back seats. No, no, I mean I get to be honest. I can confess my thoughts. They know the worst I have to offer. I mean, I'm gonna show this to 'em. ESSAY II This piece, originally titled "Soldier Son," first appeared in 1997 in New Letters, a literary journal at the University of Missouri. It was later reprinted by the Utne Reader. I had been to parties here before, a slightly stuffy, pleasantly scruffy London flat with worn leather on the chairs, Kurdish rugs on the floor and etchings of worthy ruins on the walls. It looked like a grownup version of Cambridge "digs," and most of us looked like middle-aged versions of the Cambridge undergraduates we had mostly been, now pundits and publishers, writers and actors, what the British call the "chattering classes." Both my sons were with me on this trip, 16-year-old Alex out with his guitar and the punks of Piccadilly Circus, 19-year-old Tim somewhere in the adjoining room in Harris tweed. I recognized the man crossing toward me, glass in hand, as somebody I vaguely knew, first name Jeff (or Geoff), last name lost. I remembered he was witty, articulate, an impassioned campaigner for free speech; my kind of person. So I was glad to see him headed toward me. He charged a little purposefully, though, his look heated. "I've been talking to your son," he said and set his glass against his chin. "My God, how do you stand it?" My stomach clenched around its undigested canapes. Shame, defensiveness and rage (I am responsible for my son; I am not responsible for my son; who are you to insult my son?) so filled my throat that I could not speak. The free speech champion offered me the kind of face, sympathy and shock compounded, that one offers to the victim of mortal news. "I manage," I managed presently and turned on my heel. I have never run into Jeff again, but I credit him with the defining moment, when choice is made at depth: the Mother Moment. Let's be clear. I live in knee-jerk land, impulses pacifist to liberal, religion somewhere between atheist and ecumenical, inclined to quibble and hair-split with my friends, who, however, are all Democrats and Labour, who believe that sexual orientation is nobody's business, that intolerance is the world's scourge, that corporate power is a global danger, that war is always cruel and almost always pointless, that guns kill people. My son Tim, who describes himself as a fiscal conservative but social liberal, shares these attitudes of tolerance toward sex, race and religion. His politics, however, emanate from a spirit of gravity rather than irony. Now 33, he is a member of the Young Republicans, the National Rifle Association and the U.S. Army Reserve, with which he spends as much time as he can wangle, most recently in Bosnia, Germany and the Republic of Central Africa. I love this young man deeply and deeply admire about three-quarters of his qualities. For the rest - well, Jungian philosopher James Hillman has somewhere acknowledged those parts of every life that you can't fix, escape or reconcile yourself to. How you manage those parts, he doesn't say. What Tim and I do is let slide, laugh, mark a boundary with the smallest gesture, back off, embrace or shrug. Certainly we deny. Often we are rueful. I don't think there is ever any doubt about the "we." Most parents must sooner or later, more or less explicitly, face this paradox: If I had an Identikit to construct a child, is this the child I'd make? No, no way. Would I trade this child for that one? No, no way. This week in Florida I receive in the mail a flier from Teddy Kennedy that asks me to put my money where my mouth is, assuming my mouth is saying, "Yes! I will stand up and be counted to help end the gun violence that plagues our country." I am considering a contribution when Tim drops by. He is headed to the gun show, thinking he will maybe indulge himself with a Ruger because it's a good price, has a lovely piece of cherry on the handle and fine scoring, and he's never had a cowboy-type gun. He's curious how it handles, heavy as it is. Later he comes back to show it off. He fingers the wood grain and the metalwork, displays the bluing on the trigger mechanism exactly as I would show off the weave of a Galway tweed, the draping quality of crepe cut on the bias. He offers it on the palms of both hands, and I weigh it on mine, gingerly. It's neat, I admit. Grinning at my caution, he takes it back. I have a black and white snapshot of Tim and his little brother, both towheaded and long-lashed, squatting in an orchard full of daffodils. I also own a color photograph, taken in the African savanna, of Tim, grown, kneeling over the carcass of a wild boar. Now, looking at the toddler in the daffodils, I can see the clear lineaments of the hunter's face. But squatting beside him years ago, I had no premonition of which planes, tilts, colors of that cherub head would survive. Looking back, I can see clearly in his passion for little plastic planes, tank kits, bags of khaki- colored soldiers and history books about famous battles that his direction was early set. But I was a first-time parent. I thought all boys played soldier. Alex liked little planes, too, but he went into other fantasies, to Dungeons and Dragons and from thence to pacifism and the Society for Creative Anachronism. In him, I have witnessed the astonishing but quite usual transformation from radical-punk-anarchist to responsible, loving husband and father. Tim's journey has been otherwise: As a child he was modest, intense, fiercely honorable and had few but deep friendships. He lit with enthusiasm for his most demanding teachers, praising their strictness. He was from the beginning a worrier after his integrity, which he pursued with solemn doggedness, eyes popping. In puberty, Tim developed no interest in sports but kept a keen eye on world news. He read voraciously, mostly adventure novels, admired John Wayne's acting and politics, and more than once quoted "My country, right or wrong." At 18 he came home in tears because he could not go to defend England's honor in the Falklands. I was grateful for the friend who told him, "You know, it isn't that we're shocked. All of us are familiar with the attitudes you have; we've considered and rejected them." Tim swallowed and said, "I didn't think of it that way." Since then he has thought of it in several hundred ways, and so have I. I'm aware of my contradictions in his presence: a feminist often charmed by machismo, a pacifist with a temper, an ironist moved by rhetoric that can be Hemingwayesque. His humor can be heavy-handed. He can be quick to bristle and on occasion hidden far back in himself. These faults unfold his virtues: You could trust him with a secret on which your life depended; neither will he betray you in trivial ways. He would, literally, lay down his life for a cause or a friend. He is, of American types, pre- Vietnam. Tim doesn't expect a weapon for his birthday, and I don't defend Jimmy Carter in his presence. But sometimes we stumble into uneasy territory. We have learned to acknowledge that, mother and child, we not only don't share a world view; we cannot respect each other's. Our task is to love in the absence of that respect. It's a tall order. We agree that we do pretty well. Stating the impasse seems, paradoxically, to confirm our respect. Tim has this observation: "It's a good thing it's you who's the liberal, Mom. If I were the parent, I wouldn't want to let you be you the way you've let me be me." Two things are at work here: Motherhood is thicker than politics, and a politics of certainty - the snap judgment, closed mind, blanket dismissal - cannot be what I mean by liberal. To love deeply where you deeply disagree creates a double vision that impinges daily in unexpected ways. The mail and the gun show were on Saturday. Sunday afternoon Tim is back to show me a double-cowhide holster he has cut, tooled and stitched freehand. "It's a pretty fair copy of John Wayne's favorite; he called it his Rio Bravo." "It's handsome," I say. I don't say that it's also delicate, with bursts of flowerets burned around the curve of the holster front and the loop that holds it to the leg. Tim shows me deep cuts in his index fingers from pulling the beeswaxed linen thread through hand-punched holes. All those years while I taught my boys to iron and sew, I thought I was turning out little feminists. He has another gun to show me. I forget the name of this one, a semiautomatic from which, he carefully shows me, he has removed the clip. He has spent several hundred hours filing every edge inside and out so all the parts fit with silken smoothness and the barrel shines blackly. This is the hammer and the seer, the housing, the clip well. This is the site he's got an idea how to improve. This is the handle he has crosshatched with hair's-width grooves to perfect the grip. Just so do I worry my lines across the page one at a time, take apart and refit the housing of sentences, polish and shine. This is love of craft he's talking. This is a weapon that could kill a person that I am holding in my hand. The conflict between conviction and maternal love stirs again, stressfully. ESSAY III Burroway submitted this essay to the St. Petersburg Times a few days ago. I have today canceled the subscription of my son Timothy Alan Eysselinck to American Rifleman and removed his name from the National Rifle Association mailing lists, lobbying efforts, fund solicitations and so forth. Tim has been a lifetime member of the NRA, a registered Republican, an avid hunter of small and big game, a Ranger and a captain in the U.S. Army, and a civilian contractor for humanitarian de-mining. Because he was deployed or employed all over the world, his NRA mail still comes to the house in Tallahassee where he grew up, but as he shot and killed himself on April 23, the messages are no longer received. I have been looking over the most recent issue of Rifleman trying to grasp why a fiercely honorable boy fell in love with objects manufactured to destroy, and why such boys continue to believe that such objects foster integrity and peace. But my mind is not adequate to the task, and the magazine is not intended to explain to the unconverted. Tim was a loving and obedient child fascinated with all things military, tactical, strategic, ballistic. He could spend hours repositioning the limbs of a plastic soldier or reproducing the patina of wear on a toy ammo belt. As a teenager, he sought discipline and rigor, to the wonder of my friends. He took a degree in history as a member of the ROTC, then spent four years stationed in the Army in Hawaii, where he described himself as a "warrior without a war." He left to become a security officer for the embassies and multinationals in Cameroon, and as a Reserve officer headquartered in Stuttgart, he was sent to Bosnia, the Republic of Congo, and then to Namibia, where he learned expertise in de-mining. In Windhoek, Namibia's capital, he married on the eve of the millennium, became a stepfather and later a father to a daughter now 31/2. In August of last year, having completed a two-year humanitarian de-mining project on the Ethiopian-Eritrean border (the family spent that time in Addis Ababa), Tim was offered his choice of a desk job in Washington or a mine-clearing contract in Iraq. His wife agreed to return to Windhoek and honor his desire for a limited tour at the front. In Baghdad, Tim headed a $7-million project with eight civilian colleagues, a dog team and 90 Iraqis, who, he said, were the best he'd ever worked with - the most dedicated, the most disciplined. They gave him hope for the governmental handover because Sunni, Shiite and Kurd, they worked side by side in mortal danger with mutual trust. In the Green Zone and in the field, Tim carried two pistols and a machine gun; I'm sorry to report that I paid no attention to what kind or caliber. He spent his days blowing things up - some mines, but more often unexploded ordnance from American cluster bombs - to clear building sites for housing and schools, and in one instance, a soccer field. In January, my son came to Tallahassee for a day, en route from Namibia back to Baghdad by way of a de-mining conference in Tampa. He was gorgeous in Iraqi guise - tan, bearded and finally with a full head of hair. My husband, Peter, said I fell in love with him all over again. The three of us shared the strangeness of Tim's brother, Alex - that eternal pacifist - now being on the front line as supervisor of the Piccadilly Circus station of the London Underground, not only chasing buskers from the tunnels where he used to busk but, uniformed, drilling his crew in antiterrorist evacuation. Tim was missing his family and thought his Iraqi team on the verge of self-sufficiency. But he also worried that it would become targets of the insurgents, and he was despondent and enraged at the Bush administration and the Bremer regime - "the corruption, the incompetence, the greed, the lies, the brute stupidity." I confess I was elated to hear this. I did not then know (because he wouldn't worry Mom with too much truth) that one of his men had lost a leg in a de-mining accident, nor that their compound was fired on daily - nor that he had been treated for depression in Ethiopia the year before. Nor did I suspect that his plane would lift out of Baghdad weaving to dodge a missile. I had, like a good liberal mom, let him choose his views and his life, and now it seemed that firsthand experience was bringing him round to mine. With better hindsight, my brother pointed out, "Tim was someone who thought that with ideals and a gun you could fix things." He had put his life at the service of a government that stood on just such a belief, and his disillusionment cut deep. Back in Iraq, a note in his appointment calendar for Jan. 10 reads "all mistakes anyway everything crazy now I hope I can make it home safe." In late February, Tim completed his tour and rejoined his family, and he spent a couple of weeks in the jubilation of freedom. But his re-entry to the low-level chaos of family life was hard. He was obsessively irritable in small ways. He became a news junkie. Madrid was attacked, the Spanish pulled out of Iraq, Fallujah fell apart, hostages were taken. If all the contractors left, how could there be reconstruction? Tim's work would have come to nothing but danger for the troops who trusted him. He obsessively e-mailed his men, but they were busy staying alive and answered at a lag, if at all. He solaced himself with hunting on a game farm in Namibia, sending proud pictures of himself with a downed warthog, a springbok, a magnificent kudu. Then, on April 22, hunting with an unfamiliar rifle in the wrong light, he wounded a gemsbok he could not track. On his return, inconsolable, he told his stepson that he had found a tooth, which meant that he had hit the animal in the face. He had had to leave it, like his men in Iraq, to its fate. Tim shot himself the next evening in the dining room of his house in the Windhoek hills called Eros. It was a clean kill. The trajectory took the bullet through the right maxilla, upper left cranium, a black and beige Herrera-pattered drape, and out a rectangular window pane. A week later, Alex stood in front of that window on his way to his brother's funeral in full McKenzie kilt regalia, bringing together the Scottish heritage of which Tim had been so proud and his choice of Africa as homeland. No one will ever know what exploded in Tim's mind. And no one will know how many children for decades to come in Namibia, Angola, Ethiopia, Eritrea and Iraq will retain all four limbs because my kid who loved weapons accidentally stumbled into the profession of getting rid of them. We do know, however, from the Namibian police, that the last gun he held was a .45-caliber Norinco model 1911 (nicknamed "Government"), serial number 901233. They pried it from his cold, dead hand. -- Janet Burroway is the Robert O. Lawton Distinguished Professor Emerita at Florida State University and the author of novels, plays, stories and essays. Her most recent book of essays is Embalming Mom, published in 2002 by the University of Iowa Press. Her play Parts of Speech will be produced in March at Florida State. |

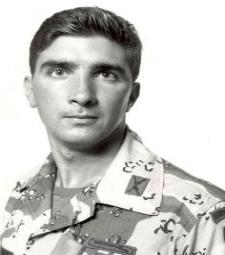

| American Contractors in Iraq and Afghanistan Casualties Not Counted Tim Eysselinck |

| Eysselinck Vs. Ronco Consulting/CNA PTSD Injustice Prevails read here |

| An interview with the mother and widow of a former Iraqi contractor “I feel that there has been an enormous betrayal of truth and principle” The Other Victims of Battlefield Stress; Defense Contractors’ Mental Health Neglected "There is a huge percentage of contractors who are silently suffering," Eysselinck said. "That obviously puts them and their families at risk. Communities are bearing the brunt of this, especially the families." The War's Quiet Scandal Eysselinck, 44, said that neither federal judges nor insurance adjusters understand that civilian contractors face many of the same risks in Iraq and Afghanistan that soldiers do. Her husband, Tim Eysselinck, endured mortar attacks and frequently traveled across Iraq's dangerous highways, she said. |

| My son, my soldier, my sorrow In three essays written over 20 years, a liberal, pacifist mother struggles to understand her conservative son, a proud soldier and member of the NRA. By Janet Burroway |